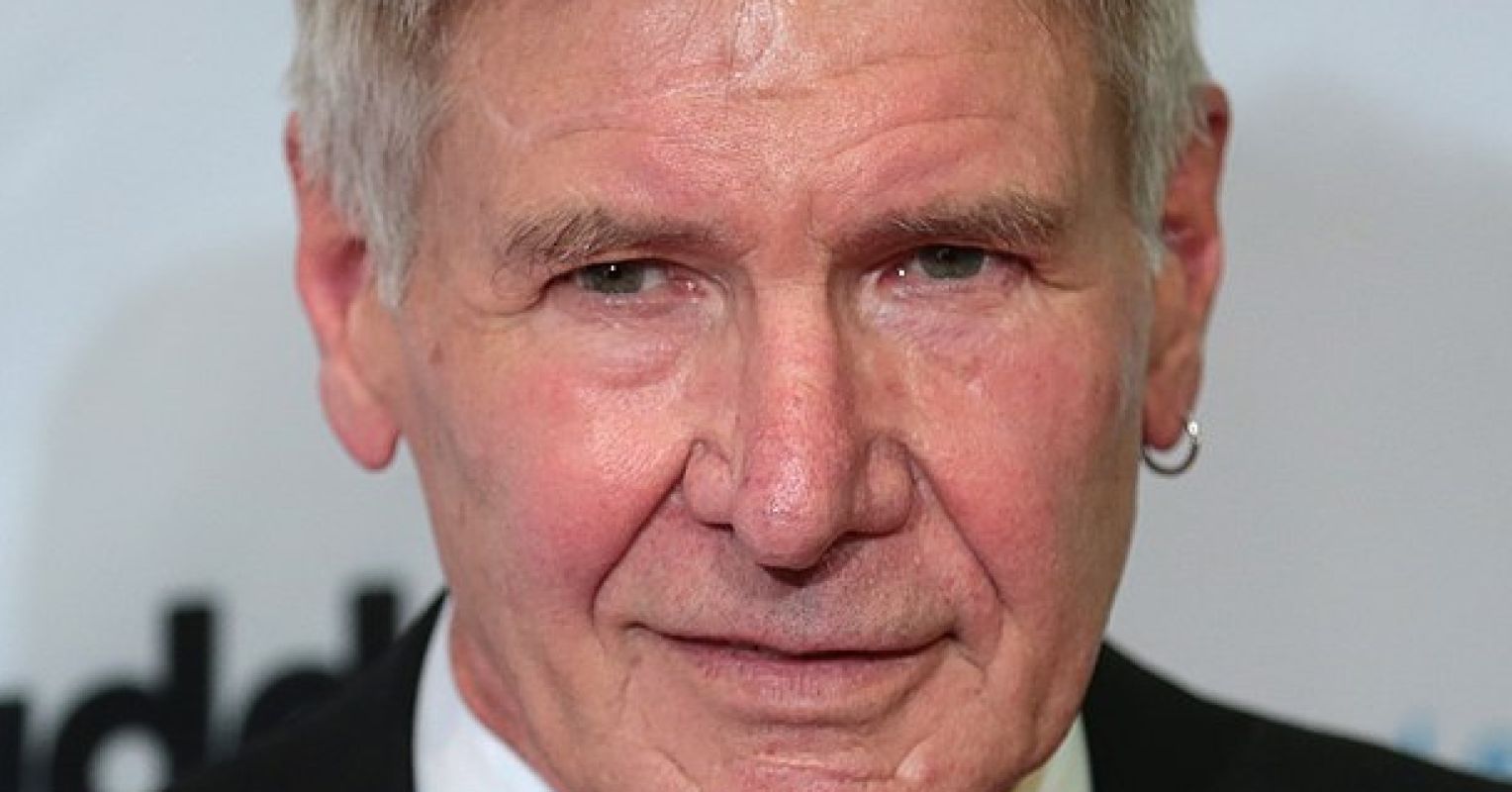

Even if you haven’t paid any attention to politics in recent weeks and months—very unlikely—you probably know of all the celebrities who lined up behind the two presidential candidates in the U.S. election (mostly behind one of them). Here is a far-from-complete but impressive list: Bad Bunny, Jennifer Aniston, Bruce Springsteen, Oprah, Jennifer Lopez, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Usher, Lizzo, Eminem, LeBron James, and, most recently, Harrison Ford.

But will it make a difference? Does it make a difference for the voter that an actor, a musician, or a basketball player supports one candidate, rather than another? Or is news about celebrity endorsements just the ultimate clickbait, appealing both to political news junkies and to celebrity gossip fans?

And if celebrity endorsements do work, why and how do they work? What is the psychology of celebrity endorsements?

I want to turn to an unlikely authority on this issue: Marcel Proust. Proust wrote his grand novel long before the age of global celebrities, but he knew a thing or two about human psychology, and society in his times was just as polarized as it is now. The main reason for this was the Dreyfus Affair.

What is now the left/right divide, the Democrat/Republican divide, or the Brexit divide was the Dreyfus Affair in the 1890s. Captain Alfred Dreyfus was a French artillery officer who was sentenced to death for treason in 1894. This verdict divided French society so much that close friendships and even marriages broke up and some of the most prestigious salons split in two over it. It didn’t help that Dreyfus was Jewish, and antisemitism played an important role in the anti-Dreyfus camp.

Proust (who was very much in the pro-Dreyfus camp) has a very insightful passage in his À La Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) on how opinions could be changed about the Dreyfus affair—in other words, on how political polarization could be overcome. It is about an aristocrat, Duc de Guermantes, who, like many of the aristocrats around him, was very much against Dreyfus.

While spending time in an elegant spa, this aristocrat met three charming and fashionable women, “an Italian princess and her two sisters-in-law.” They were all pro-Dreyfus. After a couple of weeks in the spa, the Duc returned to Paris as a Dreyfus supporter.

What changed his mind? Not rational arguments. It is very clear—like it or not—that rational arguments can almost never help us to overcome political polarization.

What changed his mind was that the three ladies were elegant, cool, and fashionable. Is this a good reason to listen to someone? Usually not. But that is what turned the Duc de Guermantes around and made him abandon his (antisemitically colored) views.

For the record, the ladies were right: Dreyfus was innocent and the documents that triggered his sentencing were forgeries. So superficial things like elegance or fashion can sometimes give us a push in the right direction.

And this is the way celebrity endorsements work (if they do work). But Proust’s story also gives us some clues about just when they work and when they don’t.

They work if the celebrities have some kind of a cross-divide appeal: if they don’t only appeal to the part of the society who is already on board. So a George Clooney endorsement, say, is probably not going to move the needle much: everybody knows already what side he is on and people on the other side may just dismiss him as a leftie hack. Someone like Harrison Ford, on the other hand, may give an endorsement that matters; he is someone who may be more likely to appeal to both sides of the political divide.

As with the three fashionable ladies, what matters is not what he says, but who it is who says it.